Week 3 — Prototype

This week is programming week, and the challenge activity is to create an interactive ‘grey box’ prototype.

We’re encouraged to use 3rd party assets and libraries, and I found a WIP card game framework which I can build upon. My own WIP source code is available on Github.

I spent the first few hours just integrating the card framework, and then I added some images and graphics from previous drawings. What you see here is the card game framework and some static graphics. I have also developed a mood board on Miro.

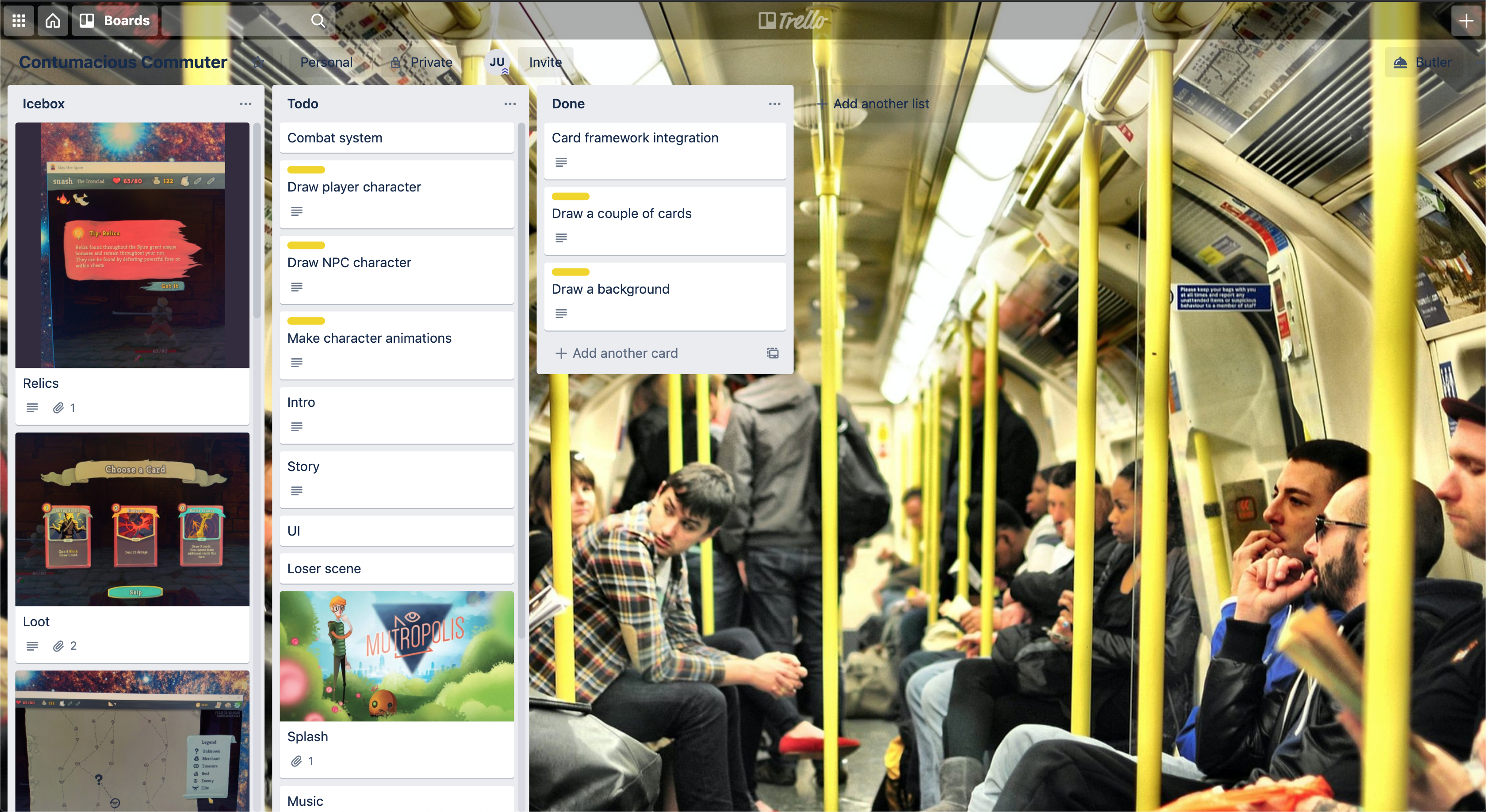

What comes next is to develop modules to coordinate combat using a turn queue, and taking care to decouple the UI. I have set up a Trello board to remind me of which tasks need completing, but also to capture moon-shot ideas for if/when the game grows beyond this module.

Pre-production VS production

I want to discuss Mark Cerny’s “Method” and a couple of Jesse Schell’s rules of thumb for making games.

I’m following Mark Cerny’s Method, in which I’ll treat the next 10 weeks as chaotic pre-production (as opposed to production), during which I’ll try and “capture the lightning” and aim to have a “publishable” first playable (Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences 2012). Some light “macro design” documentation might also come out at the other side of this, although I’ll mostly be focused on the playable vertical slice.

I’ll try and schedule many playtesting sessions, both with my perceived audience, and those outside it. This will provide an opportunity to see which parts of the game works well, and which don’t.

Cerny also states that you usually reach the end of pre-prod when 30% of the budget has been spent (McLean-Foreman 2002). Even though I’m not currently expecting to go into production with this game (maybe in the final module, or in the few off weeks leading up to the next module?), it’s an interesting metric to put the effort in perspective.

In addition to Cerny’s Method, Jesse Schell has additional two rules of thumb for getting games done on time and under budget (Schell 2019: 118):

- Plan To Cut Rule: when planning, make sure that you will build it in such a way that if 50% of the budget was removed, you could still have a shippable game

- 50% Rule: all gameplay elements should be fully playable at the half-way mark in your schedule, so you spend half the time getting the game working, and half the time making it great.

Prototypes help us answer questions

Prototyping is supposed to be a time-saving experiment in that each prototype should be designed to answer a question (Schell 2019: 109).

With this in mind, I came up with a bunch of questions to answer early on. I’ll note when I’ve already answered a question, but these are mostly open questions for the foreseeable future.

I managed to parallelise a couple of my prototypes by coding during the times when I’m awake and fresh, and drawing the art while I’m hanging out with the kids and supposed to be away from screens, which is a great way to get more prototyping loops done (Schell 2019: 110).

Who is the game for?

As always, I’m making the game for myself. The initial audience I’m targeting are players of Slay The Spire (Megacrit 2017) and the commuter demographic who also plays video games. I’m not sure how much of an overlap there is between these two demographics, and if it really matters, but I’ll narrow the audience down during the next 10 weeks.

Task: get the prototype in front of STS players and commuters often throughout the process.

How can I make the game fun or interesting to play?

We’ll look further afield for inspiration (e.g. historical art books, articles and studies about commuting, etc), but this might lie in a striking new art style, a different/interesting vibe, a twist on a popular genre or mechanic, etc.

I might try and bend the card mechanic a little?

- instead of turn-based, make it continuous

- allow time slow-down, for the player to think (maybe only when the enemy attacks)

Perhaps I can introduce whacky comedy, or slapstick, and at least have the game be hella funny even if it’s not a great card game. This could be effected by dialogue, story, funny animations, and whacky interactions.

Nobody has ever died in any of my games, and nobody will die in this game. Foe NPCs will have an annoyance meter (instead of a health meter) and once they’re suitably annoyed, they get off the train. There’s some wiggle room for comedic effect here.

Task: implement a continuous time mechanic (with “bullet time”) and see if it’s novel enough and still makes for a compelling gameplay experience.

Task: inject a special flavour of comedy and see if the audience likes it. Try different flavours.

Which art style will work best?

(I know it’s programming week, but I had to take a break and make something look nice.)

I like to illustrate and colour with watercolours, so I’ve come up with a bunch of art mockups/prototypes already. The wife and kids like it. My friends like it. (They’re all very polite, you see.) I might stick with this style for a while longer and try and develop it a bit more.

No remaining tasks for this question, other than maybe getting it in front of more people.

I’ve identified a risk with the art in that it will take ages to hand-draw all the character animations, so I came up with two possible workarounds:

Art workaround 1

The hand-drawn illustrations will be replaced with a low-poly workflow to speed up production:

Task: incorporate one low-poly Blender animation with cel/outline shaders applied into the game and see if it looks good and if folks like it

Art workaround 2

Don’t animate, but instead switch between different hand-drawn poses, e.g. from idle pose to shocked pose (angry face, arms up or in defensive position)

I can even boost workaround 2 a bit by implementing a shader which will turn all the black outlines into SquiggleVision.

Task: make a prototype where I switch between character poses instead of animating to see if it still looks compelling, or if the game doesn’t lose any wow-factor.

Task: then also try the above with a SquiggleVision shader.

How will the game performance be?

I wouldn’t need to benchmark anything, as it will be a simple game, with not many objects on the screen. I do plan to run many simulations, once I have all the cards designed (in terms of cost/effects/etc, not art) so I can tweak the balance, so perhaps I need to take special care designing the game in a way that it can be easily unit-tested and exercised by a simulator.

Task: check if the game can be designed to be unit-testable, and easily simulate-able.

I think I might have an answer for this already, as the card framework already comes with an extensive suite of tests.

Can I integrate a card game framework and save time?

A card game uses complex mechanics, so the more time I can save, the better. As long as I understand the framework well enough to customise it.

This was a question I answered early on, as it’s the most important part of the game. As mentioned, I found a card framework asset I could build on, and I’ve already customised it a bit to get it running as in the screenshot above.

Is the toy fun?

A ball is a toy, but baseball is a game. You should make sure that your toy is fun to play with before you design a game around it.

(Schell 2019: 113)

Shuffling the cards, dealing a hand, and moving the telegraphing arrow around the screen is already fun and looks good, so this is a promising base for the game to build on.

In fact, the toy perspective is such an important one, that Schell made it one of his lenses, “The Lens Of The Toy”:

To use this lens, stop thinking about whether your game is fun to play, and start thinking about whether it is fun to play *with*.

Ask yourself these questions:- If my game had no goal, would it be fun at all?

(Schell 2019: 113)

- When people see my game, do they want to start interacting with it, even before they know what to do?

Conclusion

I have a bunch of other questions, but the next 10 weeks are all about pre-production, and there will be plenty of time to answer them.

Echoing Schell, Renaud Forestié reminds us to minimise scope, as “it’s really about putting the minimum effort possible to do what works” (Unity 2018).

TBH, I’m not breaking entirely new ground in terms of technology, so there are no prototypes to answer those “what if” type questions.

Bibliography

- MCLEAN-FOREMAN, John. 2002. “Conversations From GDC Europe: Mark Cerny, Jonty Barnes, Jason Kingsley.” Available at: https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131368/conversations_from_gdc_europe_.php [accessed 6 Feb 2021].

- MEGACRIT. 2017. “Slay The Spire.” Available at: https://www.megacrit.com/ [accessed 30 Nov 2020].

- SCHELL, Jesse. 2019. The Art of Game Design: a Book of Lenses. Third edition. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, a CRC title, part of the Taylor & Francis imprint, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group, the academic division of T&F Informa, plc.

- ACADEMY OF INTERACTIVE ARTS & SCIENCES. 2012. “D.I.C.E. Summit 2002 - Mark Cerny.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOAW9ioWAvE [accessed 6 Feb 2021].

- UNITY. 2018. “Best Practices for Fast Game Design in Unity - Unite LA.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NU29QKag8a0 [accessed 6 Feb 2021].

This post is part of my critical reflective journal and was written during week 3 of the module game development.

Unlabelled images are Copyright 2020 Juan M Uys, and are for decorative purposes only.