Week 6 — MVP and prototype progress

- Proof of concept 1

- Proof of concept 2

- Extra comments from the surveys

- Other proofs of concept

- The medium is the message

- Homework and TODO

- Lessons learned

- Bibliography

Welcome to week 6 of the module final major project. This sprint we focus on proving out our concepts, with a view to start delivering a prototype during sprint 3, which starts next week.

Quick backstory of the game:

You’re a polar bear, on her sheet of ice, floating in the ocean. Problem is, it’s the last piece of ice left in the world, and everyone wants it. Fend off the hordes.

All prototypes and works-in-progress can be found here: https://opyate.itch.io/polar

I captured some play footage of the proofs-of-concept here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fuCIKDQB9xU

Proof of concept 1

With this POC, I wanted to gauge how player movement felt. E.g. it felt a bit stiff, or could benefit from acceleration/deceleration, or “it should feel like game X”, etc.

The survey I linked to the POC had some responses, and it boils down to the controls needing more “juice”. Usually “juice” goes beyond just controls, but details all those things supporting player movement, like audio feedback, visual cues like VFX, tight animation, and such (Dutch Game Garden 2013), (grapefrukt 2012), (Game Maker’s Toolkit 2015).

Some even went as far as citing Super Mario Bros. 3 as an example of good controls to aim for. My take from this feedback is to incorporate more inertia, i.e. the player accelerates before reaching full speed, but also takes a few milliseconds to come to a full stop. The similarities probably stop here, as I’m not making a platformer with a wider range of movement types, like jumping.

Proof of concept 2

With the second proof of concept, I wanted to know: How did the player and NPC sizes feel? Unbalanced? Fair?

I’m thinking of adding a game mechanic where you can build up a flotilla using rubbish found in the sea (like driftwood, plastic, barrels, etc). This rubbish can be used to augment your weapons, and grow your floating base. A larger base would slow you down, but make your stronger.

From the survey, folks liked:

- the idea of collecting sea rubbish, as it made them feel good about cleaning up the ocean

- the idea of building up a base in the sea (these folks might just be fans of the base-building genre)

For others, the game felt a lot harder. They didn’t feel as agile or nimble. The challenge here would be to scale up fire-power in tandem with player size.

A concern of my own was that the player character would feel sluggish, and loose the fast-paced excitement of the early game. As this is an abstract world anyway, I’m thinking of keeping the player movement speed and agility to keep the game fast an exciting. The growing of the base serves another purpose anyway, which is that there is strength in number. More on this later.

Extra comments from the surveys

The lovely folks I surveyed were kind enough to offer up extra suggestions and comments beyond those that I asked for:

- they’d like to see the protagonist, finally. Everyone’s clamouring for the polar bear!

- the little red squares that gets dropped when enemies perish: those seem like a bad thing at first because of the colour red. (I chose red to make it stand out from the blue sea background, but will play with other colours)

- getting swarmed too quickly. (The game is not at all balanced right now, but I might pay some attention to this sooner rather than later.)

- the progress bars at the top are confusing. (I’ve since moved the health bar to the player, and will make it very clear that the top bar is for levelling up.)

- this game reminds them of other eco-critical games like Frostpunk, Endling, etc because of similar themes.

Other proofs of concept

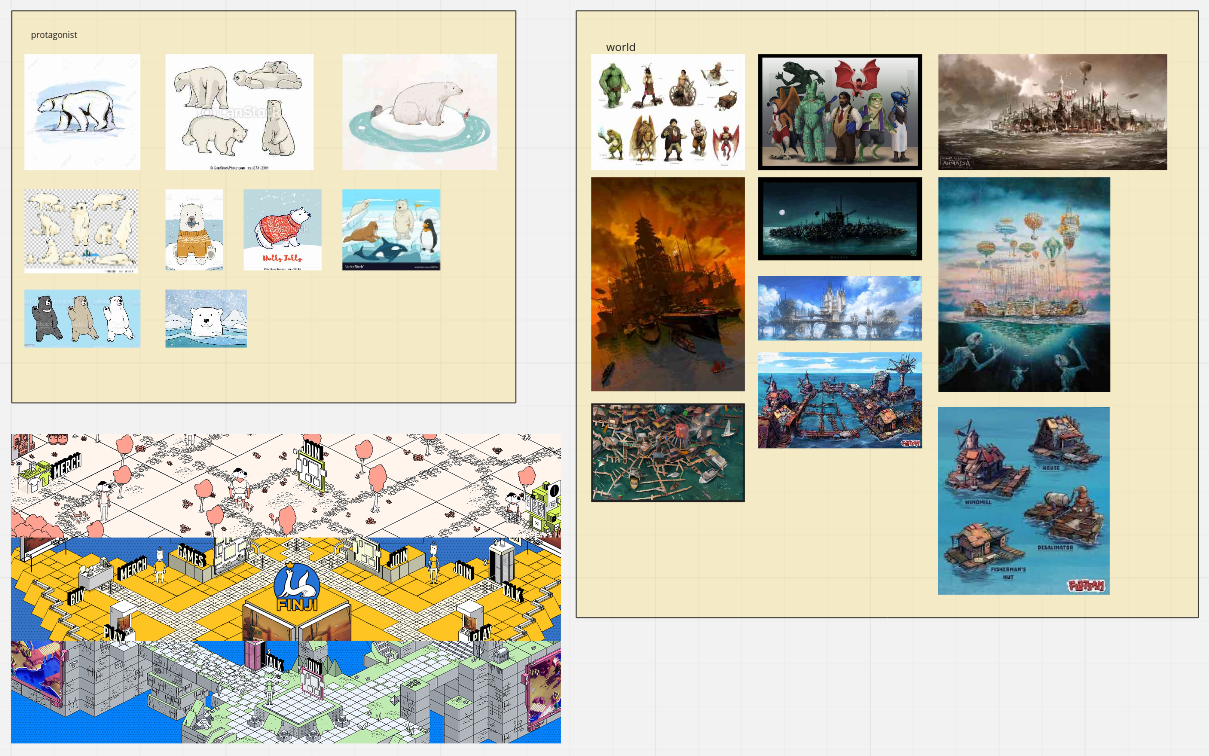

I have some miro boards and pen & paper sketches, to thrash out some ideas around art and look & feel, before I commit to making art electronically.

Miro board

I’m inspired by China Miéville’s The Scar, not just the giant floating armada, but also the “new weird”-ness of it.

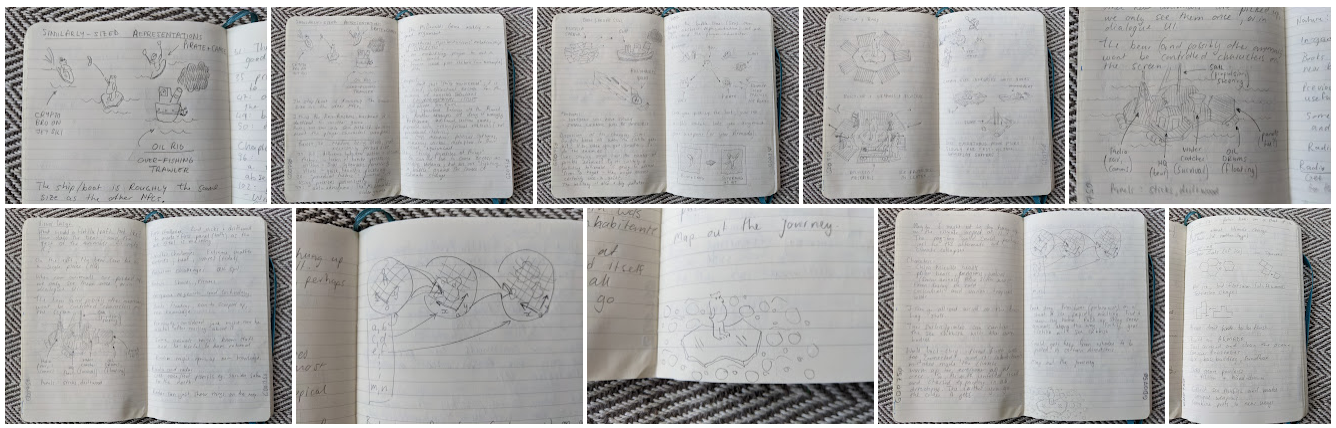

Sketches

Pen & paper helps me to visualise characters and settings and juxtapose them before committing to pixels.

The medium is the message

The game will have at its core an important message about climate change, and have various factors which will be in support of the message:

- the polar bear is on a sheet of ice, and it’s the last sheet of ice in the world

- the sea is full of rubbish

- sea rubbish can be recycled to make new things (new weapons, ammunition, or extra parts for the flotilla)

- the enemies will be polluting, like noisy motorboats, drippy oil tankers, military (a known big polluter), etc

- extreme weather will threaten the raft and its crew, like heat waves (which also threatens the ice), tidal waves, storms, etc

- the raft will pick up other strays in search of a new icy home, and this will reinforce the message that there is strength in numbers

We don’t want an unsubtle, heavy-handed, didactic message.

The idea of “the mechanic/medium is the message” is further underpinned by ideas from literature:

- Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric

- Doris Rusch’s experiential metaphor

- Steve Swink’s metaphor metric

We’ll discuss each in turn, and then align them all at the end, with other supportive and counter-arguments.

Steve Swink’s metaphor metric

As a component of a game feel system, metaphor has two aspects, **representation** and **treatment**.

**Representation** is the idea of the thing, or what it appears to be. [...] If you replace all the art, music and sound in a game with purely abstract shapes and colors, what you have removed is the **representation**.

Imagine the game Diablo with graphics by Jackson Pollack and sound by Steve Reich. The fundamental functionality of the game is still intact, but the metaphorical **representation** is gone. While dribbles of paint and electronic pulses do not really represent anything, barbarians, buildings and cows give each object in the game some hook on which players can hang their conceptual hats.

**Treatment** is the cohesive whole formed by visual art, visual effects, sound effects, tactile effects and music. If you take away all the art, music and sound from the game but leave the core systems untouched, what you have removed is the **treatment**.

Imagine the game Diablo with every object - avatars, townsfolk, creatures, environment - replaced by flat gray boxes. The fundamental functionality of the game is still intact, but both treatment and representation are gone.

(Swink 2009)

An example for the game: sea rubbish, even if it benefits the player when picking it up (for crafting weapons and a larger raft), has to look like sea rubbish. It can’t just be abstract gems or coins that make a counter go up.

To think about: What does the control scheme convey? How much does it sell, or communicate the experience that you’re this particular avatar.

Doris Rusch’s experiential metaphor

Rusch introduces the term “experiential metaphor” for the phenomenon of understanding a gameplay experience as a physical visualisation of abstract ideas such as emotional processes or mental states. What the game feels like can provide an additional interpretative cue that helps game comprehension along (e.g. game feels like relationship, thus it might be about relationship).

Games can evoke strong associations to experiences from real life along the lines of “oh my, this feels exactly like (insert appropriate experience here)!”.

(Rusch 2017)

An example for the game: feeling helplessness when the sea fills up with too many oil spills or rubbish. Feeling anger when the polluters come after you or your last piece of ice. And especially, the last piece of ice on earth is due to global warming, and this will make the player feel sad for the bear. But not just feeling feelings, but feeling like you’re in a battle to save Mother Earth.

Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric

According to Bogost (2007), procedural rhetoric is interested in the ways that ethical, political and social arguments can be embedded in the rules of a game, and how the rules are communicated to, and understood by a player. Via their simulation rules, games present embedded values, and it is the players’ appropriation and understanding of that model that make a game have meaning (Zagar 2013).

An example for the game: the player collects rubbish from the sea; the player stands up against polluting enemies.

Bringing it together

Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric, Doris Rusch’s experiential metaphor, and Steve Swink’s metaphor metric are all aligned toward the idea that “the mechanic is the message” or “the medium is the message”. If I want to communicate a message, it has got to be through a well-tuned mechanic, and appropriate aesthetics, all the while conveying a suitable set of emotions in the player to hopefully mobilise them to fight climate change.

Going beyond procedurality, Sicart argues that the designer should leave enough room for player appropriation and self-expression, and not force a viewpoint onto the player through the game’s procedurality:

Against the argument of efficiency and rationality, we should invoke the aesthetics of play, the ethics of expression, the myth in the machine. To surpass instrumental play and address that whatever games contribute with to our culture, play cannot be codified; it cannot be limited and bound to the processes delimited by arbitrarily created rules dictated by distant designers. Play belongs to players, and the games’ meaning resides in the actions of players.

(Sicart 2011)

An example for the game: the game can also offer choices: you can choose to fit more polluting weapons that are stronger against the enemy, but then you become a part of the polluting problem. (I would, however, be mindful of weaponry in the game, and not be labelled as inciting eco-terrorism like Thunderbird Strike was (Starkey 2017), although any PR is good PR, I guess!)

Nelson offers a critique of Sicart’s paper, or perhaps an alternative-yet-complementing viewpoint, and says

"Meaningful games" should not be modelled on rhetorical theory but on performance-art theory. Rather than attempting to convey meaning or persuade via representation of arguments in processes, one ought rather to design games aimed at setting up meaningful situations or effecting interventions.

(Nelson 2012)

Homework and TODO

Apart from what I’ve done so far, there is still a lot more:

- be careful with the firing projectiles, and don’t get accused of ecoterrorism like the lady from Thunderbird Strike. We might have to be very metaphorical about “weapons” in the game.

- Research climate change solutions. See if they can be used as “weapons” in the game.

- missing piece: the argument. What do I want to persuade people of? E.g. causes of the problem (causing the polar icecaps to melt, sea levels to rise), and then: here is a response to this problem (give the player a real solution to the problem; how can I mobilise players?)

- the notion of building is the opposite of melting - can this juxtaposition be used to full effect?

- Research: Find horde survival game that builds, or has building mechanic. (base building) The closest I’ve come to far are TD games (tower defence). But with TD, you’re not building a base, as such, but you’re adding towers to it along pre-determined paths.

- merry group of bandits: feels more like a united front, collective action, against climate change. Convey the idea that there is power in numbers.

- more sustainable ammunition: Boomerang, harpoons on ropes, perhaps large floaty boulders which can be collected again after it knocks an enemy out? As I’m inspired by the New Weird of China Miéville, perhaps there can be some thaumaturgists onboard with special magical weapons.

In fact, I’ve put this up for discussion with my cohort:

I’ve thought about introducing sustainable weapons in the past, e.g. boomerangs (infinitely re-usable), or any weapon, really, which you don’t let go off (chain mace / flail, or other such medieval weapons you can think of), which ties into the don’t-pollute / recycle messaging.

I had a thought that you can give the player the option to craft/pick-up “stronger” weapons, but the trade-off would be that they’re more polluting, so you become part of the problem. (Proper military weapons, explody things - we all know the military or war in general is one of the biggest polluters.)

This ties into Miguel Sicart’s “against procedurality” (as in Bogost’s “procedural rhetoric”) of giving the player more options, and not shoe-horning them into the designer’s intended message with procedurality. Giving the player more agency to make their own choices, and all that. I.e. they don’t have to play like an eco warrior who recycles and don’t pollute; they can go all-out postal with nukes if they want.

I’m still keeping Thunderbird Strike in the back of my mind, trying to be careful of the “inciting eco-terrorism” badge. (Although, that might be FABULOUS PR for me…)

If a player plays more greenly, they can be appropriately rewarded for it.

Meanwhile, I’m also trying to think really hard about not having weapons at all. E.g. bring in China Miéville’s “new weird”ness back into it, perhaps the polar bear can be a thaumaturgist who can magic up some blocks of ice around enemies, freezing them. Or she can summon tornadoes or tidal waves (extreme weather!) to float the enemies away. Or summon a Kraken which eats them (the Kraken is mad anyway at those bozos for polluting their watery home). Or if we have to use real weapons, perhaps having “soft” weapons that don’t kill, like whips.

I’d miss having projectiles, though, as it’s so cool to see them flying across the screen…

Sorry, I’m yammering! Let me know your thoughts.

Lessons learned

Prototype VS proof of concept (POC)

I started off calling the proofs-of-concept prototypes, but they are different:

POC shows that a product idea can be made, and the prototype shows how it’s made.

Pen & paper VS game engine

We were urged to not use our final game engine of choice for the POCs, but I just jumped straight into Godot. TBH, the coding comes naturally, and with years of experience, I tend to structure my work well from the get-go, so I’m basically “sketching with code”. The engine doesn’t get in the way at all.

In future, I will consider using something other than a game engine for POCs, but for the two proofs-of-concept I discussed above, I still feel that using a game engine was the best choice, as especially the first POC deals with player movement in the game, and they can both be shared more easily electronically. Paper prototypes can be scanned and shown to folks electronically, but work better when a visual concept has to be communicated, not gameplay.

Bibliography

- BOGOST, Ian. 2007. Persuasive Games the Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Available at: http://site.ebrary.com/id/10190451 [accessed 7 Mar 2022].

- NELSON, Mark J. 2012. “Sicart’s ’Against Procedurality’ \Textbar Mark J. Nelson.” Mark J. Nelson. Available at: https://www.kmjn.org/notes/sicart_against_proceduralism.html [accessed 7 Mar 2022].

- RUSCH, Doris C. 2017. Making Deep Games: Designing Games with Meaning and Purpose. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business.

- SICART, Miguel. 2011. “Against Procedurality.” Game Studies 11(3), [online]. Available at: http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap/ [accessed 7 Mar 2022].

- STARKEY, Daniel. 2017. “No, This Video Game Is Not ‘Eco-Terrorism.’” The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/11/1/16588166/game-ecoterrorism-politics-thunderbird [accessed 7 Mar 2022].

- SWINK, Steve. 2009. Game Feel: a Game Designer’s Guide to Virtual Sensation. Amsterdam ; Boston: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers/Elsevier.

- ZAGAR, Catherine. 2013. “Procedural Rhetoric and Instrumental Play: Value and Meaning in Simulated City-Building.” AMNESIALOG. Available at: https://amnesialog.wordpress.com/2013/01/14/procedural-rhetoric-and-instrumental-play-value-and-meaning-in-simulated-city-building/ [accessed 7 Mar 2022].

- DUTCH GAME GARDEN. 2013. “Jan Willem Nijman - Vlambeer - ‘The Art of Screenshake’ at INDIGO Classes 2013.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AJdEqssNZ-U [accessed 6 Mar 2022].

- GAME MAKER’S TOOLKIT. 2015. “Secrets of Game Feel and Juice.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=216_5nu4aVQ [accessed 6 Mar 2022].

- GRAPEFRUKT. 2012. “Juice It or Lose It - a Talk by Martin Jonasson & Petri Purho.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fy0aCDmgnxg [accessed 6 Mar 2022].

This post is part of my critical reflective journal and was written during week 6 of the module final major project.

Unlabelled images are Copyright 2020 Juan M Uys, and are for decorative purposes only.