Week 4 — Narrative design

Reviewers of video games, jaded and blunt, make no bones about their low expectations for narrative quality in the products they critique for a living. Clunky story structure, uneven pacing, cliché-ridden characters, and painful dialogue are expected norms, almost unworthy of comment. In fact, it’s only when a game manages to miraculously rise above this low quality bar and present plot, character, and dialogue on par with, say, a direct-to-disc movie that reviewers and players might sit up and take notice.

(Skolnick 2014)

The week 4 challenge activity asks us to formulate a narrative design document for our prototype.

The narrative design doc is a living document, but I will reflect on the current-at-the-time-of-writing-this version (Git commit hash 71b5983) of the document here:

https://github.com/juanuys/ccgdd/blob/71b5983/narrative.md

Fantasy

A couple of weeks ago we were asked to come up with a player fantasy, but I felt this was too soon and that fleshing out the story first would help with coming up with a fantasy. But, before there is a game story, there are always previously established elements, such as genre, core mechanics, and context (Skolnick 2014). As it turns out, one can come up with a fantasy knowing only genre, core mechanics, and context. But, after I had my narrative doc done, I came up with one more fantasy which in retrospect feels like a fantasy players could potentially care less about.

Fantasy based on genre, core mechanics, and context:

I’m a commuter on the receiving end of pushes, shoves, loud music and smelly food. This game will let me fight back!

Fantasy based on the story:

I’m a loving pet owner, and my pet is kidnapped, and I go on a hero’s journey to retrieve them.

Inspirations and prior work

The “infractions on public transport” idea has been bouncing around in my head since 2016. In fact, the first version of the game was made with Unity, targeted mobile, and used a connect-3 one-handed play mechanic to execute attacks with. So, a game about commuting, targeted at commuters. It even came with a barebones GDD.

Unity since blew up in my face, and 2 years hence (in 2018) was when I first thought of perhaps skipping digital technology altogether and making a card game. However, during this module we have to make a video game, which brings us to the current moment.

I’ve since revamped the story (the purpose of this week, and hence this blog post) and drew inspiration from

- “dark” weird, like China Miéville’s New Weird, especially the Bas-Lag series, and more generally urban fantasy

- “not-so-dark” weird, like Adventure Time

- Art Deco architecture and organic form

- Mattias Adolfsson’s illustrations

What has helped is a narrative design course I did on Coursera a few months before starting this masters. (In fact, here is an exercise where we had to storify a game which only had a hint of story to begin with.)

Reflection: tying characters together

I re-wrote the story a couple of times. In the first version, the protagonist would just encounter random foes on the train. In the latest version, the main antagonist sends their friends (secondary antagonists) to confront the protagonist. I felt like this tightened the story a bit, and made the player care more about defeating the secondary antagonists.

Ernest Adams states “coherence” and “dramatic meaningfulness” as requirements of a good story, in that the events in the story must not be irrelevant or arbitrary, but must harmonise to create a pleasing whole (Adams 2014: 211). He goes on to say that some might get away with including material that doesn’t appear to belong in their story if they are trying to make a surrealist or absurdist point, so it’s good to know I have some wiggle room for madness in my urban fantasy.

Reflection: foes - more of the same?

In the story the protagonist finds a photograph which shows the faces of all the secondary antagonists, alongside that of the main one. I’m a bit concerned that each antagonist might just be more of the same, i.e. what will differentiate them? I suppose this is a problem I will solve when we do the character design module later on.

What I do not want is undue repetition in this game (Adams 2014: 212).

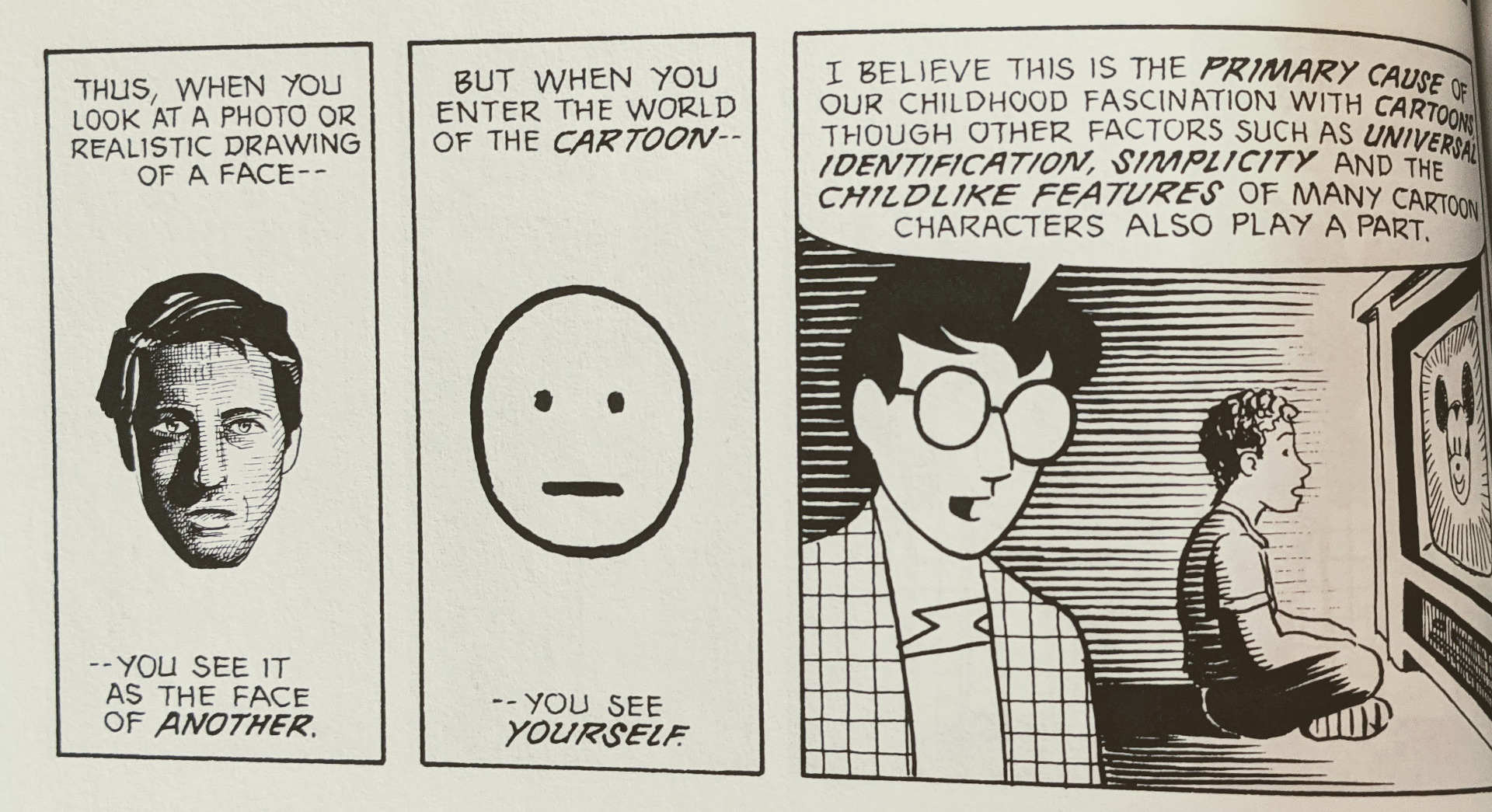

Reflection: cartoony VS realistic

I grew up with comics, from the safe Archie, then Kuifje, then all the way to Lobo in my teens. Even today I’m very much into graphical novels, like The Nao Of Brown or the new Dune.

I’ve always preferred abstract over realistic depictions of characters, and Scott McCloud agrees: (Katherine Isbister also echoes this sentiment, funnily enough ALSO on page 36 of her book (Isbister 2017: 36))

Thus, when you look at a photo or a realistic drawing of a face, you see it as the face of another.

(McCloud 2017: 36)

But, when you enter the world of the cartoon, you see yourself.

For these reasons, I’m naturally drawn to produce abstract art as opposed to realistic art, and it should be easier to produce.

Reflection: a game for change?

From my narrative design document’s Theme section, I state a goal of the game:

The second goal is to teach humanity that, look, these are the various things that people do on public transport, and it’s utterly annoying, so please stop doing it. Hopefully it will show people what not to do on public transport, and be kinder.

Is there scope here to make a “game for change”? I know I’m not solving world poverty or giving minorities more voice, but if folks can end up being a bit kinder on public transport, then I’d be happy.

Reflection: linear or branching?

Linear stories are simpler (it requires less content, and are less prone to bugs and absurdities like continuity errors) (Adams 2014: 221), and having it works best here, as I don’t want to develop systems to support open worlds and branching narratives. I’d rather focus on the card mechanic, and have a suitably entertaining story to carry us forth.

The story is linear and the player will experience it linearly. There is no choice in character customisation, and player agency is somewhat curtailed as they can’t influence how the overarching story plays out (Adams 2014: 222). I might consider a branching map where the player can choose which encounter to do next, and choosing between one foe or another. As such, the game would be mostly “game story dominant” but bordering on “balanced” due to the possible choices offered by the journey map (Skolnick 2014).

Reflection: innovative?

There might be an innovation here, as most video card games rely on typical “fantasy” tropes like swords for fighting, and magic, monstery monsters. Back in 2018 I also thought that “card game set on a train” might be quite novel, but it’s not anymore!

Reflection: that time I felt I didn’t need stories

I remember a time, not so long ago, when I said sacrilegious things like

Narrative, nil so far, and possibly nil in the future.

I was immersed in puzzle game mechanics at some point and my mind just blanked on narrative. In retrospect, I’m very much for narrative design, and love coming up with worlds, characters and stories.

Besides, a story provides greater emotional satisfaction by providing a sense of progress toward a dramatically meaningful, rather than abstract, goal (Adams 2014: 208). Adams also goes on to say that stories attract a wider audience, helps keep players interested in long games (puzzle games are short games, and a story will feel intrusive, and players only really care about getting a high score at that point), and help sells the game.

Reflection: too much story?

E.M. Forster distinguished between flat and round characters in Aspects of the Novel (Forster 1985: 75). It’s common practice to create character checklists when developing a novel or other piece of creative writing, e.g. physical/biological (age, height, size, state of health, etc), psychological (intelligence, temperament, attitudes, self-knowledge, etc), interpersonal/cultural (family, friends, colleagues, etc) and personal history (major life events, including happiest and most traumatic) (Anderson 2006: 74).

Even though there’s a lot of stuff in the narrative design doc, I also felt it necessary to define as much of the characters and game world as possible, even if I don’t end up using it. It helps filling plot gaps, and extra lore underpins what players see in the world, and helps the designers and developers have a common reference when questions are asked about the characters, world and story. (Heussner 2015)

Reflection: connection with the protagonist

I have found that in some of the card games I’ve played, since I’m not in control of the protagonist, I feel a bit detached from them, and they’re almost just like an NPC, just there on the screen. I’m hoping that giving the protagonist more of a story will make the player feel more connected to them. This will be magnified by the comics in-between the battles which feature more of the protagonist’s story.

Reflection: the hero’s journey

In the narrative design document’s Plot section, the story starts off with the protagonist already on the train, albeit having a hard time. Borrowing terms from Vogler (Vogler and Montez 2020: 99-116), public transport is the hero’s weakness or “tragic flaw”. When they get back home, they’re a “wounded hero”, but their companion re-energises them. Home is the “ordinary world” and public transport is the “special world”.

The “ordinary world” would be in the top half of Dan Harmon’s story circle, and the “special world” in the bottom half (Will Schoder 2016).

I am concerned that the “special world” isn’t special enough since we see it in the opening scene. I might spend some more time to find a way to foreshadow the “special world” instead of having the protagonist in it from the get-go.

Perhaps the protagonist could have vowed never to get on a train, because a dear parent has succumbed to their demise on public transport. However, this will change the companion’s role, as they don’t re-energise the “wounded hero” after their journeys.

Anyway, food for thought. The answer might become more apparent when I actually implement the story in the game.

Bibliography

- ANDERSON, Linda (ed.). 2006. Creative Writing: a Workbook with Readings. New York: Routledge.

- ADAMS, Ernest. 2014. Fundamentals of Game Design. Third edition. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

- FORSTER, E. M. 1985. Aspects of the Novel. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- HEUSSNER, Tobias. 2015. The Game Narrative Toolbox. New York: Focal Press/Taylor & Francis Group.

- ISBISTER, Katherine. 2017. How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design. First MIT Press paperback edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The MIT Press.

- MCCLOUD, Scott. 2017. Understanding Comics. Reprint. New York: William Morrow, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

- SKOLNICK, Evan. 2014. Video Game Storytelling: What Every Developer Needs to Know about Narrative Techniques. Berkeley: Watson-Guptill.

- VOGLER, Christopher and Michele MONTEZ. 2020. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Fourth edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions.

- WILL SCHODER. 2016. “Every Story Is the Same.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LuD2Aa0zFiA&feature=youtu.be [accessed 19 Feb 2021].

This post is part of my critical reflective journal and was written during week 4 of the module game development.

Unlabelled images are Copyright 2020 Juan M Uys, and are for decorative purposes only.