Coursera - Game Design Document - define the art & concepts, continued

I’ve started CalArts’ Game Design Document - define the art & concepts and here are my course notes for weeks 2 up to 7.

Week 2

Prototyping

A prototype is a playable version of the game. Like the pen & paper games we created in the introductory course. The game flowchart from the narrative course, or the world map from the world design course could also be seen as playable prototypes. Another popular way to get player feedback is via alpha releases (although the instructor thinks it might disrupt production).

A non-exhaustive list of ways to prototype a game:

- 3D game engines

- 2D game engines

- simple game engines (e.g. RPGMaker or Twine)

- mod kits

- board/card games: helps with game flow, helps you understand how major events in the storyline affect/effect gameplay, and a great help for level design

- flowcharts: visualise flow; begin at the start of your game/story, and map each level or story point as a box in your flowchart. Each box can simply be the name of the level, and use it to refer back to your story; it follows your story’s chronology; for setting up cause/effect situations

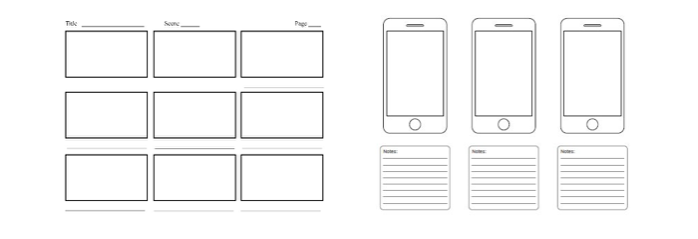

- storyboarding: the panels usually follow the aspect ratio of your target device; each panel describes an action, with accompanying text below it; tells the story in the script/treatment/synopsis

Playtesting can surface two types of issues:

- technical: Technical problems will keep on manifesting themselves all the way through development and commonly even after release. As you make changes, bugs, glitches and crashes will occur. Taking care of them as they appear will keep you from being overwhelmed by them.

- creative: Creative issues make up the other major category of feedback. Gameplay might not be fun, the story problematic, the atmosphere may be confusing or distracting, etc. These deeper issues might emerge at different times during the playtesting process, but most of them should be addressed before the game is released. Remedying these issues is tricky. All of the game’s ideas, like story, gameplay and aesthetic, are intertwined and can have an impact on the rest of the game.

Here’s a good playtesting checklist, also summarised below:

- Concept Testing takes place early on in the process and is all about ideas proofing and experimentations.

- Scattershot Testing is where you start testing games mechanics one by one and see if they work in context.

- Experience Testing focuses on the values of the game experience itself. Is the game fun?

- Gameplay Stress Testing is where technical issues, glitches and “exploits” (breaking the game to your advantage as a player) happen.

- Accessibility Testing is fundamental as you’re putting your game in more people’s hands. Is it playable and accessible to anyone regardless of ability (or at least your targeted audience)?

I’m skipping notes for week 3, as it’s basically a week during which you have to refine your GDD (and your prototype).

Week 4: Visualisation

Visualisation is getting into the look, feel and sound of your game. Keep researching, updating your mood boards and asset folders, gather your visuals and sounds, and start refining them into the vision of your game.

The experience: while playing a video game three senses are triggered: vision, hearing and touch, but what does the player retain from it? Your objective is to make your creation a memorable experience. You want the player to retain memories. E.g. sights you won’t forget, muscle memory from repetitive playing, or emotional impact.

Week 5: The experience, continued

With digital distribution, we’ve lost boxes and manuals, standing in line at the video game store, blowing into the cartridge, etc. How can we rekindle this? Studios and publishers are looking to bring fans content such as soundtracks, art books, figurines, or other bonus materials to build a tangible connection with the games they love.

Some publishers go even further with connecting the real world and the game world. Fallout 4 and its “Pip-Boy edition”, for instance, have built a non-traditional experience into the gameplay itself. A player can transform their their smartphone into a gameplay component and use it as a mechanism to access their inventory.

The game Keep Talking and Nobody Explode forces players to cooperate in order to defuse a bomb. One person has access to the device on a screen and describes what is seen while others are frenetically searching through a manual. This back and forth between two levels of interaction is what makes the whole game a memorable experience.

The retro dev scene creates games for “dead” systems (ones that are not supported by their hardware manufacturer) like Sega Genesis or Dreamcast. Some are made only for arcades or conventions in a setting involving a particular disposition like Line Wobbler or Killer Queen. This makes the user experience specific to that device.

Week 6

A game design document is an encyclopedia of your game’s aesthetics and goals. At its core, the primary components for it are, a synopsis of your game story, a description of your game play, and something that describes the look and feel of your world and its characters.

More tips:

- start off with a strong opener (spine)

- describe your story by showing the characters (synopsis)

- organise the information so it flows easily

- use descriptive text, and back it up with striking artwork

Get people to play your game.

Week 7 was just a review week.

Conclusion

All throughout the weeks, we had the opportunity to submit a more polished GDD to be peer reviewed. I submitted one in week 1, and didn’t get any feedback for quite a while. Then I realised that all the weeks’ assignments were optional save for the final submission in week 6 (with week 7 being just a review week). Which means I ended up not submitting anything for weeks 2-5, because I really wanted to get feedback for week 1 and incorporate suggestions in week 2’s submission and so forth. I submitted the final week, and got the usual range of feedback, e.g. single-worded “good” etc. I ended up passing the course and getting the specialisation, and guess what - I’m still waiting for feedback for week 1. Oh, well.

So, what did I learn in this course?

The playtesting checklist teased out the different kinds of testing, whereas previously I would just bundle these all together. Having a software engineering background, I’m used to all manner of testing: unit/integration tests written by ourselves (the devs), QA being done by a separate team (looking for bugs, checking software meets acceptance criteria), and UX testing (where we the dev team sit behind a one-way mirror and watch on as someone uses our website or app). I guess game testing is different in many ways, one of them being: if the GDD says “player should be able to jump twice their height”, then it is a requirement, but if the playtesters come back and say “jumping twice my height doesn’t feel right”, then one can’t argue with that. So it’s a bit more like UX testing in the web development sense.

Make the game memorable (see weeks 4 and 5).

That’s it. Now let’s go forth and make some more games!