Game analysis

Week 2 covers game design (collective YAY!), and the spark challenge is to analyse an inspiring game in terms of these criteria. I conclude with final thoughts on what makes this game special.

There is a great number of very good games I’ve played over the years, but since I’m planning to make a card game, I thought I’d analyse one: Slay The Spire.

Game Mechanics

These are typically the things that the player can do in the game. Some game mechanics operate on a moment-to-moment timescale, for example running and jumping, while others have a longer timescale, for example completing a level might happen every few minutes.

(Falmouth n.d.)

Actions in the battle scenes are represented by cards, which the player “plays” by dragging it onto the battle area from the “hand” at the bottom of the screen. When defeating a monster, the player collects spoils, which may include more gold, potions, or adding a card to their deck. In the map scene, the player can choose which branch of the path to explore next, and choices are monsters (or elite monsters with better wards), camp (to heal or upgrade), merchant (to buy new cards, relics, potions, or remove cards from deck), or unknown location denoted by a question mark (random one of an event, a monster, the merchant, or a treasure Room) (Smith 2017). An event is a bit of lore which presents the player with more buffs and upgrades.

The game is a constant balancing act of not reaching zero health, but advancing to upgrade cards, get more potions, collect more relics, and boost attributes (like maximum health).

Genre

Games that rely on the same tropes and game mechanics are frequently grouped together into genres. Often these tropes originate from one or two foundational games, for example id Software’s Doom and QUAKE, in the case of first-person-shooters.

(Falmouth n.d.)

Deck building + roguelike.

There are countless good deck building games in the non-digital sphere, like Dominion, whereas something like Magic requires you to build your deck before starting a game. I prefer making difficult decisions in-game (former), rather than before-hand (latter).

Roguelikes are characterised by permadeath and procedurally generated dungeons (McHugh 2018), although there are more appropriate labels like roguelike-like or rogue-lite for games that veer a bit from the categorisations (Bycer 2019).

Player Fantasy

What wish is the game fulfilling for the player? Does it give them a chance to experience something they can’t do in the real world?

(Falmouth n.d.)

“I’m an adventurer in search of treasure which can be found in dangerous dungeons where I battle monsters with my might and magic.”

Platform and Controls

What hardware is the player using to view and interact with the game? How are the player’s inputs converted into actions within the game?

(Falmouth n.d.)

- PC (Microsoft Windows, macOS, Linux) -> keyboard + mouse

- Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Xbox One -> DPad controller

- iOS, Android -> gestures

Spatial Abstraction

How is space represented in the game? Is it three-dimensional or two-dimensional? Is the space divided into fixed grid squares, like a chess board, or is it a more realistic simulation of the real world?

(Falmouth n.d.)

A two-dimensional (2D) staging space for the characters using a cartoonified representation of the locations in the spire. (I use “staging space” instead of “play space” as the player doesn’t interact/use the avatar directly, but rather via the cards.) The map represents a physical map, and the player can select the next waypoint using the controller (or tapping), instead of navigating their avatar there.

Avatar

What represents the player in the game? Are they controlling a particular character or object, or are they more of a disembodied overseer?

(Falmouth n.d.)

The player is represented by one of four avatars in the 2D staging space, controlled by the hand of cards next to the staging space (Ramos 2019).

Camera Perspective

How does the player view the game world? Are they looking through the eyes of their avatar, or from behind or above them? Is the camera free-moving or locked on a particular plane and angle?

(Falmouth n.d.)

A locked side view with both avatar and enemies (facing off) visible in the staging space. The backgrounds are hand-drawn cartoony locations in the spire which seem to use single-point perspective to add a bit of depth.

Goals and Scores

Giving the player something to aim towards is key to keeping them engaged in the experience.

(Falmouth n.d.)

The ultimate goal is to traverse the various levels of the spire, battling enemies on the way, and ultimately defeating the boss on every level.

Gather points towards unlocking new characters or new relics and cards. Up to 20 Ascension difficulty levels unlock with each successfully completed run, each adding a cumulative negative effect such as lower health or stronger enemy attacks.

There are metagames, like traversing the tower using only their starting relic or without adding any rare cards to their decks, or any new cards at all. A daily challenge gives players a single chance to traverse the spire as they can under pre-set conditions and a random seed, so that each player is starts the same with the same encounters (Jones 2019).

Progression and Variety

How does the game change as the player experiences it? For example, does it get harder as you go? Does the player go on a journey to different locations? Can they unlock new abilities that modify the gameplay in some way?

(Falmouth n.d.)

The player traverses the spire, one location at a time. A location can be a battle arena, or non-battle like camps (for healing), or merchants. Each new enemy encounter poses a stronger enemy with different weapons and spells.

Tension and Rest

Very few games keep the player in a frantic state all the time – providing relaxing periods without an imminent threat is an important part of keeping the player engaged.

(Falmouth n.d.)

The game is turn based, so you can take a breather between turns to gather your thoughts and plan your next move. Also, not every location in the spire is a battle arena, e.g. you can choose a branch in your journey which takes you to a camp so you can “rest” and heal your character, if you need to.

Obstacles and Penalties

For the game to provide an element of challenge, there must be something in the way of the player that they must overcome – and often a penalty for failure. Does skill or strategy determine success? Is there a balance of risk and reward?

(Falmouth n.d.)

The player does not know what lies ahead, and every battle area of the spire reveals a new monster, or group of monsters. The elite areas has stronger monsters with better rewards when slayed. The game is turn based, so the enemies “play” as many times as you do, whether you choose to attack or not, or protect yourself or not.

The skill and strategy lies in how you build your deck, and which relics and potions you acquire. There is definitely a balance of risk and reward, e.g. you can choose to play a card which buffs you and debuffs your enemy, and then attacking to greater effect when the enemy is weaker (Dias 2018).

Resources

Currencies, crafting materials or ‘ammo’ must often be spent to perform an action, eg unlocking a new item, building a structure or using a weapon. The player may have a health resource that leads to a losing game state if depleted.

(Falmouth n.d.)

A hand is dealt from your deck at the start of every encounter, so for the duration of the battle, your deck is your most valuable resource (apart from health points, of course), and for the duration of the turn, it’s the hand you were dealt. You “spend” a card when you play it, and it goes into your discard pile. Your opponent can cast spells which effectively nullifies a card.

You can gather gold after slaying enemies, and this can be used with the merchant. You can collect or purchase relics along your journey, which are persistent, and have lasting effects (such as unique abilities) as long as you’re alive. You can also collect or purchase potions, which are single use, and can be used to increase health or buff your next attack.

Decisions

Making choices that have a meaningful impact on the game system is often a key factor in player engagement – and separates ‘deep’ games with millions of outcomes, from ‘shallow’ experiences with little player agency.

(Falmouth n.d.)

Slay The Spire offers tremendous levels player agency.

At the start of a game, the player chooses one of 4 avatars, each with unique relics, cards, and abilities.

The player chooses which new cards to add to their decks at the end of every battle. You can very easily dilute your deck if you add each and every card along the way. The player chooses whether to spend their gold on cards, relics, or potions when visiting the merchant. The player chooses which branch to take when traversing the spire, e.g. do we visit the merchant next, or battle another enemy?

And most importantly, at each turn, the player chooses which cards to play.

Simulation and Chance

What factors are beyond the player’s control? Does the game live independently of the players actions? Are their virtual ‘dice rolls’ in the game that determine how it unfolds?

(Falmouth n.d.)

The player is dealt a random hand every turn. A play-through is random as per the generated random seed for that play-through, which affects what your map looks like, which enemies you encounter, and what the merchants will have on offer. I’m not too sure if the enemy decisions are random (e.g. if they’re also dealt a restricted “hand” per turn), but they certainly seem to make educated decisions (e.g. healing instead of attacking if their health is low).

Storytelling

Firstly, what story does the game tell? Is it an adventure, a mystery or something else? Where and when does it take place, and what characters are there? Secondly, how does the game tell its story? Does it use images, cut-scenes, dialogue or gameplay?

(Falmouth n.d.)

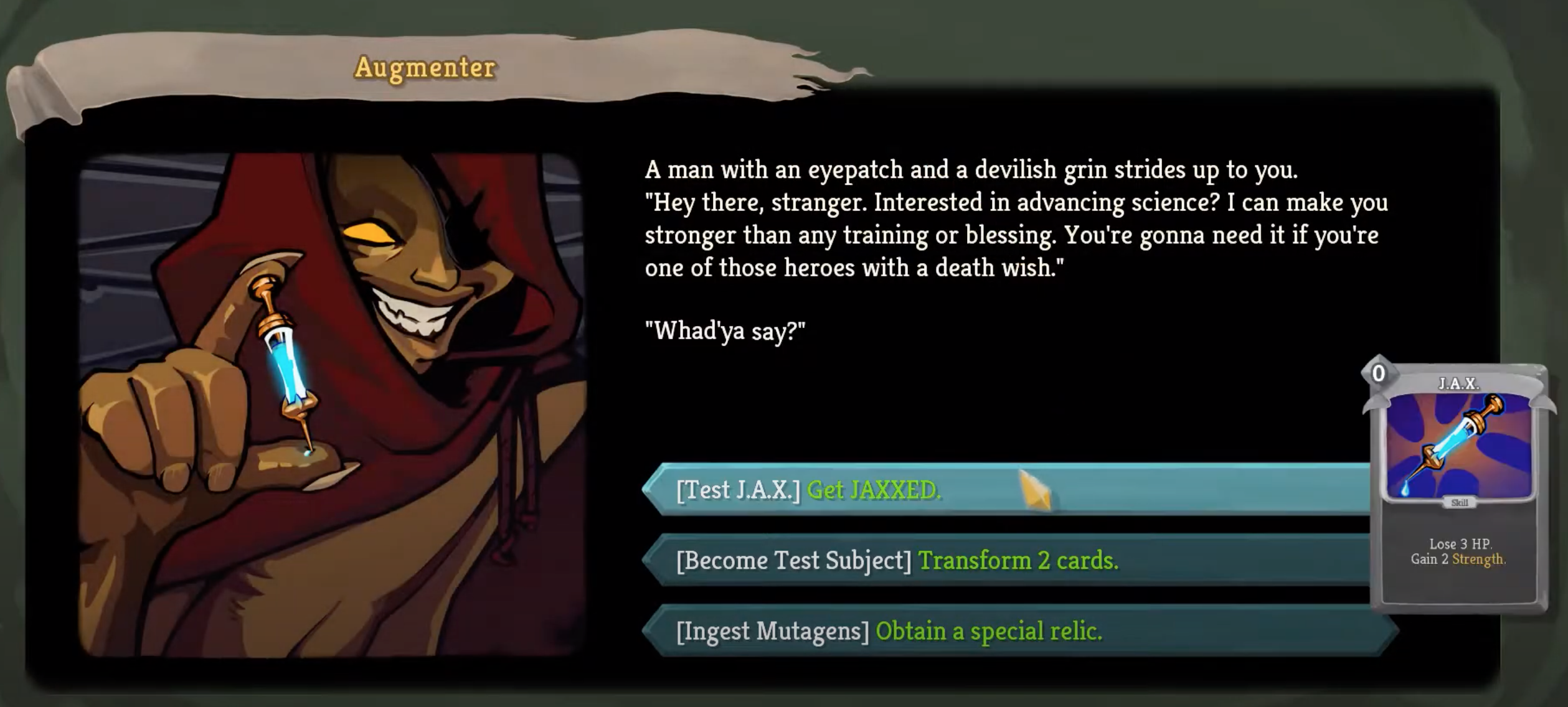

Slay The Spire is an adventure in a functional world with 3 default acts, and each act having many events (available via the unknown locations denoted by a question mark). An event can be seen as a bit of story, e.g. the Big Fish event in Act 1 where the player must select one of three goodies (buffs, upgrades, etc) dangling from the dungeon ceiling. Or, for example when you meet the Augmenter during Act 2:

Each of the 4 playable characters have a little backstory. E.g. the Ironclad

The remaining soldier of the Ironclads. Sold his soul to harness demonic energies.

(Megacrit 2017)

The merchant talks to the player (using speech bubbles, not audio) when the player interacts with his wares, but there’s no two-way dialogue. The chatter includes commentary on the wares, or commentary on the player, e.g. “I used to be like you” (Megacrit 2017).

Art Direction and Style

While not strictly a game design decision, the choice of visuals has a huge impact on how the player perceives the game.

(Falmouth n.d.)

2D hand-drawn, part-painterly, part-cartoony art style using slightly-muted pastel colours.

Dungeons have single-point perspective to give a bit of depth, and are brown, gray and gloomy.

Characters don’t have an awful lot of detail in them, but are more colourful, which works well to make them stand out from the background.

The cards are very vivid, and take center stage at the bottom of the screen.

Animation and Visual Effects

A big part of ‘selling’ the game experience to the player is the visual polish that comes from the animation of characters and objects, and visual effects such as particle systems, shaders and post-processing.

(Falmouth n.d.)

Characters (player and NPC) have basic animations for attacks and spell casting, but otherwise stay in one position throughout an encounter. Non-battle screens are mostly static.

Particle effects aplenty as attacks and spells are executed, like lightning, splatter, etc.

The hand of cards animate when you cycle from one card to the next, to clearly indicate which card might be played next. The highlighted card is telegraphed onto the enemy you want to attack (if it is an attack card). A played card flies across the screen into the discard pile.

Sound Design

How do the sound effects, environmental ambience and music set the tone of the game?

(Falmouth n.d.)

Every action has a good and appropriate sound effect, like the clanging and tearing of an attack with a weapon, or the swoosh and trickle of spells being cast.

Battle music is epic/cinematic strings with plenty of staccato. Menu music is forboding, telling of the possible gains or losses waiting on your path. When you go to the campsite to rest, you get soothing music with harp and lyre, which is a beautiful contrast to the horror that awaits you the following day.

When you visit the merchant, the music brings the following ideas to mind: teasing, almost comical, tongue-in-cheek, melodramatic, somewhat suspenseful. It uses 3/3 timing signature (unlike all the other music), which feels like you’re dancing around the merchant’s bartering skills, even though the game doesn’t include haggling as a mechanic.

Final thoughts

I first heard about Slay The Spire late 2019 when I was putting the final touches on Corn Wars, which is inspired by Slay - I was searching the web for “Slay” and the search engine autocompleted “Slay the Spire”. It wasn’t until Iain mentioned it again in a webinar late 2020 that I first played it. I was blown away.

STS is packed to the rafters with choice, a real strategist’s playground. I love card games. My family loves card games, and we play them often. Anything you can play with regular playing cards, right up to Dungeon Mayhem or Exploding Kittens.

In fact, I started converting an old game idea of mine to be a card game, and after playing STS, I decided to not make it a “collectible card game” anymore, but rather a deck-building game like STS. Which is why I’m doing a thorough analysis for STS in the next few months. I have a lot to learn before making a deck-builder, and STS is the perfect inspiration to pull from.

Bibliography

- BYCER, Josh. 2019. “The Roguelike Debate – Roguelikes vs Roguelites.” Available at: https://www.gamasutra.com/blogs/JoshBycer/20191125/354673/The_Roguelike_Debate__Roguelikes_vs_Roguelites.php [accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- DIAS, Bruno. 2018. “Slay the Spire Is a Brilliant Genre Mash-up with Third-Act Problems.” PC Gamer. Available at: https://www.pcgamer.com/slay-the-spire-is-a-brilliant-genre-mash-up-with-third-act-problems/ [accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- FALMOUTH, University. n.d. “Week 2: Introduction: Game Development IGD720 20/21 Part-Time Study Block S2.” Available at: https://flex.falmouth.ac.uk/courses/921/pages/week-2-introduction?module_item_id=47064 [accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- JONES, Ali. 2019. “Slay the Spire PC Review – the Best Solo Deck-Builder Yet.” PCGamesN. Available at: https://www.pcgamesn.com/slay-the-spire/pc-review [accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- MCHUGH, Alex. 2018. “What Is a Roguelike?” Green Man Gaming Blog. Available at: https://www.greenmangaming.com/blog/what-is-a-roguelike/ [accessed 7 Dec 2020].

- MEGACRIT. 2017. “Slay The Spire.” Available at: https://www.megacrit.com/ [accessed 30 Nov 2020].

- RAMOS, Jeff. 2019. “Slay the Spire Is My Favorite Game to Lose.” Polygon. Available at: https://www.polygon.com/reviews/2019/2/12/18220317/slay-the-spire-review-pc [accessed 30 Jan 2021].

- SMITH, Adam. 2017. “Slay The Spire Made Me Fall in Love with Deck-Building.” RockPaperShotgun. Available at: https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/slay-the-spire-deck-building [accessed 30 Jan 2021].