A Night At Locke Manor

Table of contents:

- A Night At Locke Manor

- The game

- Press release

- The Steam page

- Social media presence

- Pitch deck

- Trailer

- Bibliography

A Night At Locke Manor

2021-12-17

Team approach

A Night At Locke Manor is the title of the game we made for the IGD740 assignment. As the course was focused on the business side of gamedev, I took the prototyping mindset to developing the product, with a view to deliver something which can be used as part of a pitch to convince funders to give us money to turn the idea into a game.

As such, the game didn’t need to be a full game, but could rather get away with being elaborate smoke & mirrors (Unity 2018).

For this reason, I didn’t immediately reach for my game engine of choice, but rather made a mod using an existing engine which already specialises in the escape room experience, called Escape Simulator by Pine Studio (2021).

At the beginning of the module, I floated the idea with Maciej that I should make a gameplay prototype and that he should make an art prototype (Macklin and Sharp 2016: 184-199), because that would decouple us more and allow us to each flex their strongest skills (mine, development and design; his, art and visual design) without being blocked by other members of the team at any point (Shell’s prototyping tip #5: parallelise prototypes productively (2019: 110)).

It would also demarcate each prototype to answer its own questions (Shell’s prototyping tip #1: answer a question (2019: 109)): does my prototype prove that the gameplay works? And does Maciej’s prototype prove that the art style works?

What I delivered

Note that the below documents are just copies of said documents at the time of writing this post. The submission via the uni portal would include all the latest copies.

- v1 of our pitch deck including all text and placeholder art

- v2 of our pitch deck including including some extra sections, this time with art by Maciej

- v1 of the concept video for the game

- v1 of the trailer

- v1 of the game’s Steam page which included my gameplay prototype’s art, and placeholder art for the capsule image (snapshot 2021-12-13) (I had to remove the link to the static site for the fake Steam page, because Google got their pants in a twist and reported me as being deceptive 🤷)

- a social media presence, which only includes a Twitter account with tweets showing my own art, and a custom designed team avatar, which is a mash-up of our faces (snapshot 2021-12-13)

- press release

- v1 of studio press kit (snapshot 2021-12-13)

- v1 of game press kit using art from my gameplay prototype, and placeholder art for everything else (snapshot 2021-12-13)

- v1 of the 3-5 minute video

The reason our social media presence only includes Twitter, and not the myriad of other offerings (like Youtube, TikTok, etc), is because I’m on Twitter, and it’s the channel I feel most comfortable using. Also, as solo gamedevs or small studios, we’ll be quickly overwhelmed by community management and marketing tasks, which will leave no time for actually making games (Jonas Tyroller 2019: 11:37).

For the press kits, everyone kept recommending Rami Ismail’s presskit() to me (Ismail n.d.). It is a PHP file, however, and I don’t host a PHP site. I ended up making a tool called presskittie() that allows you to generate a static version of the press kit locally, and then optionally deploy it to Github pages (Uys 2021). With Rami’s blessing, I shared the tool with my cohort, and more widely:

Need a press kit for your #indiegame but don't have a PHP website?

— Juan Uys (@opyate) December 10, 2021

I wrapped @tha_rami's presskit() up in some fur over herehttps://t.co/MNOl3zT2eg

The game

Research

Firstly, I wanted to know about all the different puzzle types one could conceivably implement in a video game. From my own experience with games, I first came up with my own list:

- memory games, matching puzzles

- number puzzles, equations, ciphers, dates

- Logic: matching symbols, items looking out of place, repeated themes, combination puzzles

- Text puzzles: crossword, missing letters, riddles, dates

- Spatial puzzles: combining items to form new items, perspective puzzles, keys

- Light + colour puzzles: switch lights off and on, combine colours, cast shadows, UV paint or blood, differently coloured panes of glass

- Sound: clues in lyrics, clues in ambient noise, playing chimes in order, dial tones

- Hidden objects: hollowed-out books, drawers, inside anything

- Visual: clues in paintings and pictures, things looking out-of-place, jigsaws, perspective

- Electricity: circuits, buzzers, magnets

- Codes: ciphers, Morse code, musical scales, number theory

- Physics: fire + ice, weights, heat, cracking/shattering glass

Then my search expanded, and I found a a bunch of useful resources, for example:

- a Discord server which specialises in everything related to escape rooms

- a collection of topics specifically related to escape rooms, maintained by Brett Kuehner (n.d.)

- the website of one of the seemingly most vocal escape room designers, Errol Elumir (n.d.)

I spent the next few days/weeks immersing myself in the above resources.

Secondly, I set myself a goal to achieve with the game prototype, which was to make the game so intuitive, that the players will know exactly what they need to do just by playing the game, and have a clear mental model from the get-go (Macklin and Sharp 2016: 93-95).

Design

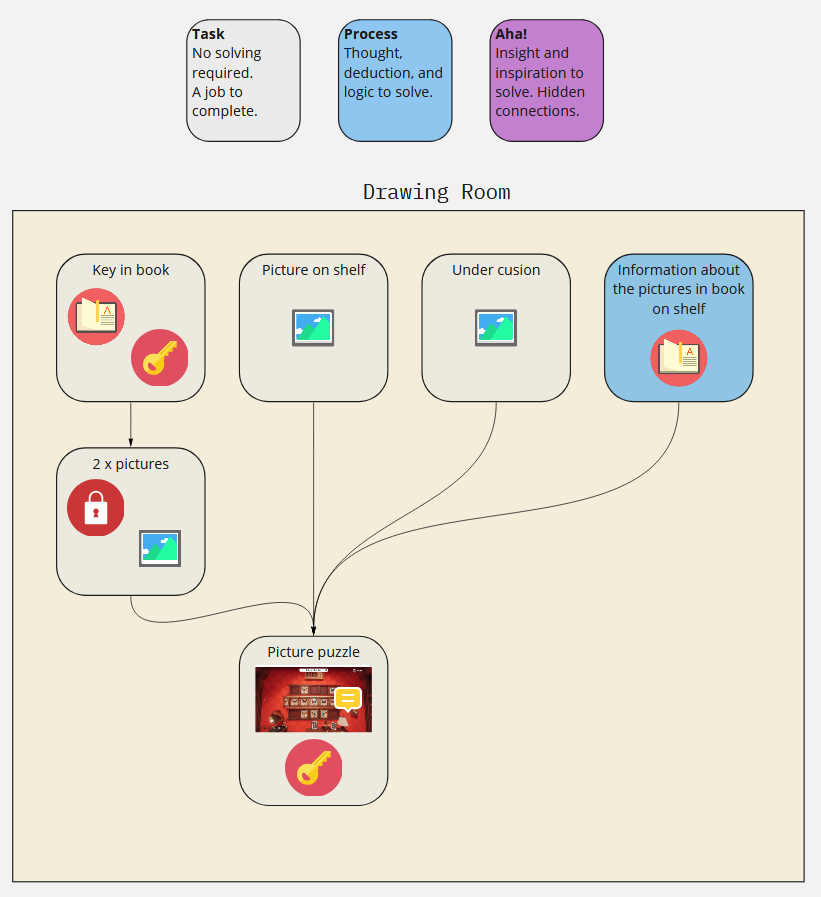

Before building anything, like implementing the level, placing all the objects (locks, keys, etc), and linking them (i.e. which cards activate which slots), I designed the puzzle using Miro (“Miro \Textbar Online Whiteboard for Visual Collaboration” n.d.). This gave me a good overview of how many keys (or Tarot cards) I would need, and how long it would take me to implement the level.

In general, I find going straight to pen & paper, or a tool like Miro, invaluable to structuring my thoughts before blocking anything out in a game engine. I was inspired by this “off-line” process years ago (back in 2007) when I learnt of the film Shoot ‘Em Up, in which writer and director Michael Davis sketched out entire animatics of the film and pitching the film as sketches via iMovie (Davis 2015).

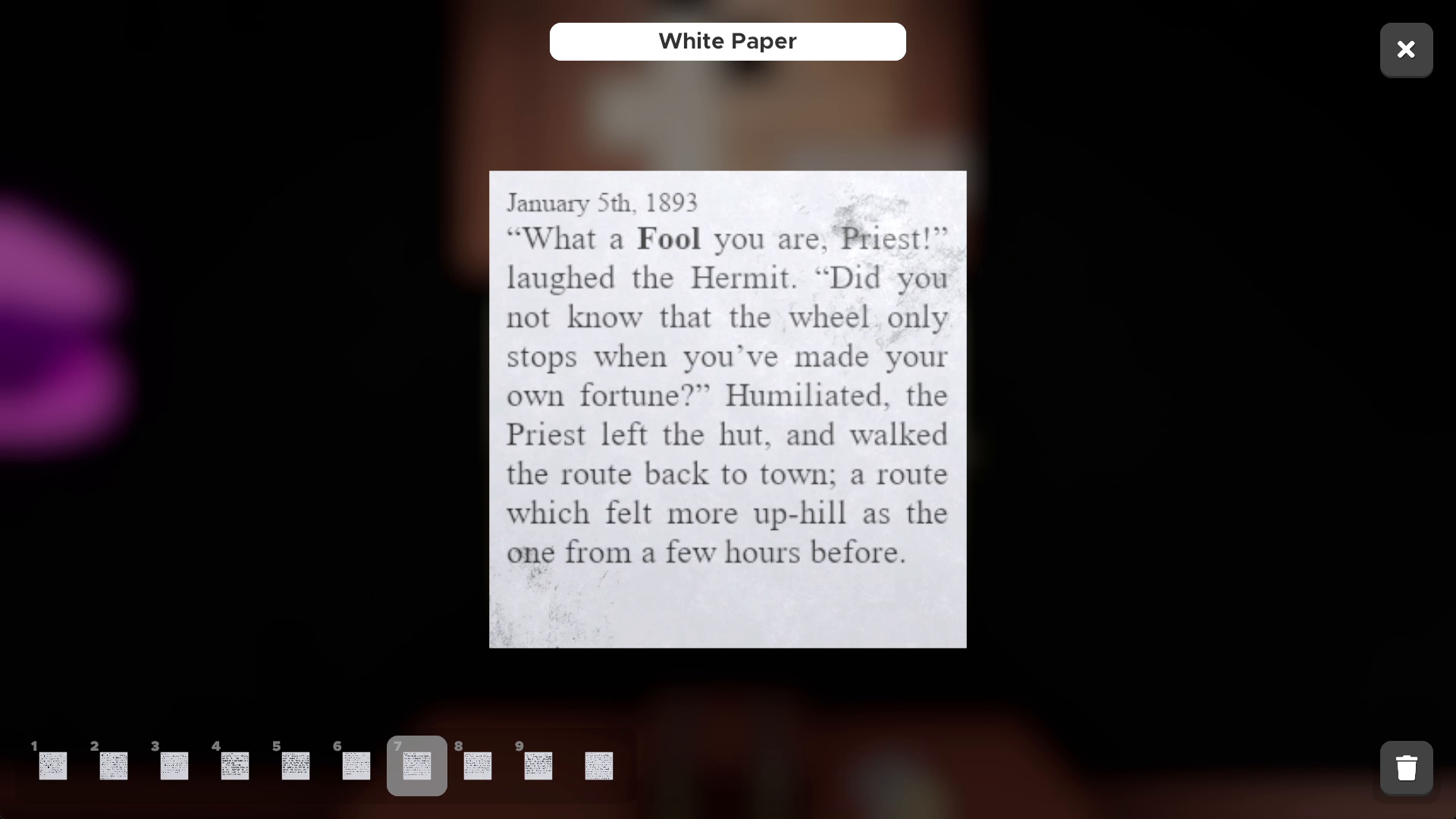

At first, I designed a more elaborate puzzle, which you first have to find a key hidden in a book, and then that key unlocks a box containing a subset of the Tarot cards (see screenshot underneath). However, I simplified the design to just be a handful of cards scattered about the room, and 8 of those cards fit in one lock, which reveals the final key.

I tied the Tarot cards to individual notes in the world, to be found by the player, and the writing for the notes was to serve as clues for the player so they know which Tarots to use, and in which order to place the Tarots.

Implementation

Apart from building a level in Escape Simulator, I did some light modding by retexturing some of the objects. Some of the textures can be seen here:

The modding engine had some limitations, in that you couldn’t have custom sound, lights, or objects. (All these are planned features, though.)

I couldn’t quite create the ambience I wanted to, but this was fine, as I only wanted to validate the gameplay.

To help me reach my goal of making the game intuitive just by playing it, I employed some family and friends as playtesters. After a couple of playtesting sessions, I think I reached a point where the start of the game is quite clear about what’s happening, and what you’re supposed to do. In fact, the game starts with you facing the door head-on, with a note stuck to the door explicitly telling you that this is the way out, and that the key is in the box to your side.

I then go on to show one of the Tarot cards already slotted into the device. The card is interactive, and you can pick it up.

Result

Gameplay video

I scripted and recorded the first 3 minutes of our gameplay video, which is available here:

Screenshots

Press release

For the press release, I tried to find the most recent best practices about wording and layout online. I mixed and matched pointers from Aaron Marsden (2018) and Alexis Santos (2018), but in the end made sure that I communicated all the most important information:

- title

- price

- availability

- logline or summary

- what the game is about

- links to press kits

- contact details

- call to action

I didn’t include too much studio information, as this press release is about the game, and the studio information can already be found online, with the link shared in the press release.

The press release isn’t addressed at any particular journalist, but any press outreach would be more personal, as this press release is really just informational.

The Steam page

For the Steam page, I took all my pointers from Chris Zukowski’s free course on how to make a Steam page (n.d.). These include:

- using verbs in the short description, as potential players want to know what they’ll be doing in the game, and don’t care about any lore yet at this point

- using the long description area (called “About this game”) to show more animated GIFs of the game, as no-one will read long textual descriptions of the game. (An established narrative-rich franchise might write more words here.)

- having one trailer which gets straight into the action. Chris references the trailer-master Derek Lieu quite heavily here, whom I’ll talk about separately. The value that Chris adds here is that he ran some experiments and saw that potential players skip through trailers until they see gameplay, as they want to quickly verify if it’s a game for them, and something they might like playing.

- choosing the right tags, so that Steam matches you with the top-selling games that inspired you. This way, if someone is searching for the known game, chances are you’ll be shown in the same search result for that game. (Please note that I made a mock-up of a Steam page, so couldn’t play around with tags until I got a desired result.)

- showing varied screenshots. You want to show different scenes and UI so the player knows your game has depth and content.

Social media presence

Wlad Marhulets recommends you choose a social media channel that you’re on already, that you’re comfortable using, and where you know the tone of voice (2020). The last thing you must do is take the same message, and post it on every social media channel. Your message will come over as flat in most places, and you’ll just end up getting ignored.

As an indie, I don’t have much time, so will be foregoing all the channels which require too much work, like video creation. That includes Youtube, TikTok, etc.

As I’m already on Twitter, I decided to create a presence there: https://twitter.com/untitled__team

Please follow that account to see all the tweets, as they are currently protected. The snapshot I shared at the start of this post won’t show any animated GIFs.

To be effective on Twitter, you need to share animated GIFs and the odd video. We upload videos natively to Twitter, instead of sharing a Youtube link, as Twitter would auto-play native videos.

Conversely, for future games, I will definitely experiment with other channels, as I discovered quite recently that Twitter consistently doesn’t work for a lot of studios, and that it’s mostly an echo chamber of gamedevs (Zukowski 2021).

Pitch deck

We went in-depth on pitching in the previous module, so I won’t re-iterate my learnings and research here. Please see that blog post for more information and the relevant citations.

Trailer

Most resources on making game trailers point to Derek Lieu’’s website (n.d.). Some of the pointers include:

- get straight to the action, and don’t bore potential players with logos, especially if you’re unknown (no-one cares about your studio logo)

- remove UI (I couldn’t do this, as I was using an inflexible modding engine)

- pay attention to pacing. Show a blast of action in the first few seconds, then cool it down, then rise again towards the end, then stop before anything is revealed (to tease), then perhaps show something funny at the end as a reward. (I couldn’t show a blast of action, as it’s not an action game, but I did attempt a little crescendo, in which you can hear the protagonist ask where they are, then looking around corners, to drive the tension up, with some tense music and the Hollywood trope of making the screen go black and hearing heart-beat sounds. I also didn’t show anything funny at the end, as it didn’t feel appropriate.)

- show verbs, and show what the player will be doing. I show the protagonist picking up objects, inspecting items, etc

- let the actions happen in sync with the music’s rhythm

There are many more guidelines and some “rules”, but in the end, these are meant to be broken, and you’re meant to be creative, otherwise all trailers would feel the same.

I made the trailer and gameplay video using a free one-week trial of Adobe Premiere, as the Mac and iMovie I usually use is getting very old and slow. I initially tried Blender’s video editing capabilities, but Blender’s engine is quite old and doesn’t benefit from GPU-powered hardware acceleration like the more modern offerings.

Bibliography

- DAVIS, Michael. 2015. “WRITERS ON WRITING: Michael Davis on Shoot ‘Em Up.” Script Magazine. Available at: https://scriptmag.com/features/writers-writing-shoot-em-up [accessed 17 Dec 2021].

- ELUMIR, Errol. n.d. “The Codex.” the Codex. Available at: https://thecodex.ca/ [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- ISMAIL, Rami. n.d. “Presskit() - Spend Time Making Games, Not Press.” Available at: https://dopresskit.com/ [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- KUEHNER, Brett. n.d. “Escape Room Design Links.” Google Docs. Available at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1lwSTxIews8azOqzHEy0vyoSrX7orx55pRImXWuBVkjU/edit?disco=AAAARqSOxKI&usp=gmail_thread&ts=618fdaed&usp=embed_facebook [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- LIEU, Derek. n.d. “How to Make a Trailer — Derek Lieu Creative - Game Trailer Editor.” Derek Lieu Creative. Available at: https://www.derek-lieu.com/start-here [accessed 20 Dec 2021].

- MACKLIN, Colleen and John SHARP. 2016. Games, Design and Play: a Detailed Approach to Iterative Game Design. First edition. Boston, MA ; San Francisco, CA: Addison-Wesley.

- MARHULETS, Wlad. 2020. Gamedev: 10 Steps to Making Your First Game Successful. 1st ed. Unfold Publishing.

- MARSDEN, Aaron. 2018. “The Last ‘How To Write A Game Dev Press Release’ Post You’Ll Ever Need.” Powerspike. Available at: https://medium.com/powerspike/the-last-how-to-write-a-game-dev-press-release-post-youll-ever-need-796aab9d7848 [accessed 20 Dec 2021].

- SANTOS, Alexis. 2018. “A Guide to Launching Indie Games, Part Three: Getting Press.” binPress. Available at: https://www.binpress.com/guide-launching-indie-games-3/ [accessed 20 Dec 2021].

- SCHELL, Jesse. 2019. The Art of Game Design: a Book of Lenses. Third edition. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, a CRC title, part of the Taylor & Francis imprint, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group, the academic division of T&F Informa, plc.

- STUDIO, Pine. 2021. “Escape Simulator.” Escape Simulator. Available at: https://escapesimulator.com [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- UYS, Juan. 2021. “Presskittie().” Available at: https://github.com/juanuys/presskittie [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- ZUKOWSKI, Chris. n.d. “How To Make A Steam Page.” Available at: https://www.progamemarketing.com/p/howtomakeasteampage [accessed 3 Dec 2021].

- ZUKOWSKI, Chris. 2021. “What Worked in 2021? A Summary of Game Dev Postmortems – How To Market A Game.” Available at: https://howtomarketagame.com/2021/12/27/what-worked-in-2021/ [accessed 28 Dec 2021].

- JONAS TYROLLER. 2019. “How to Market Your Indie Game!” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwjbLFImXOg [accessed 13 Dec 2021].

- UNITY. 2018. “Best Practices for Fast Game Design in Unity - Unite LA.” Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NU29QKag8a0 [accessed 6 Feb 2021].